02

July

2024

02

July

2024

ISET Economist Blog

Monday,

26

June,

2017

Monday,

26

June,

2017

An individual living in Kutaisi took a 1500 USD real estate secured loan from one of the microfinance institutions in 2011 and had to pay 75 USD interest rate for the following 6 months. The purpose of taking this loan was to finance treatment of her child. She was unable to cover monthly payments and prolonged the term to 10 month, but failed to cover this payments again and was fined several times. In the end, loan was restructured and monthly interest raised to 83 USD, while the amount of total loan nearly doubled to 2700 USD. As a result, she was unable to pay that much money and got an enforcement decision regarding the auction sale of her property1.

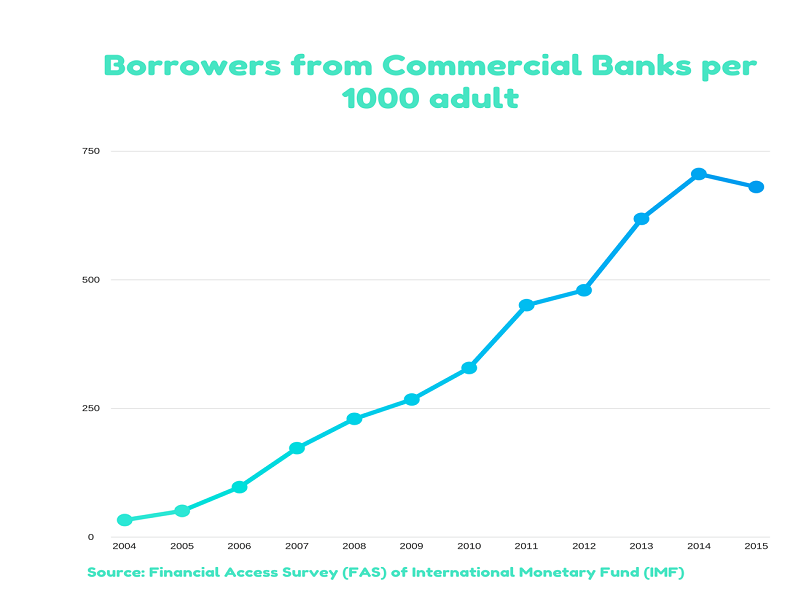

This is just one sad story of an individual entering the over-indebtedness trap, while we hear thousands of such stories nowadays in Georgia. It is widely recognized that majority of the Georgian population has debt with financial institutions, including commercial banks, microfinances and various private lenders. According to the recent Financial Access Survey (FAS) proposed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Georgia is among countries that has excessively high number of borrowers from commercial banks. It turned out that the number of borrowers per 1000 adults has already reached 680 people which is the second highest rate in the world (FAS 2015)2. It is notable that the number of borrowers was increasing steadily until 2015, when the recent economic slowdown forced commercial banks to be a little more careful while giving out loans to individuals (see graph 1 below).

Graph 1: Borrowers from Commercial Banks per 1000 adults in Georgia

In addition, according to the CEO of “Credit Info Georgia”, Aleksandre Gomiashvili, there has been a rapid expansion of registered loan contracts in recent three years. On 31 December of 2014 the number of loan contracts registered (contains individuals and legal entities) in the system was 8.5 million. This number first increased to 12.5 million by the end of 2015 and then sored to record high – 18.2 million3 by the end of 2016. Furthermore, the number of individuals that borrowed money based on these loan contracts amounted to the alarmingly high 2.4 million people by the end of 2016.

Based on these statistics one can easily estimate that nearly 64% of the total population, including juveniles and pensioners, have some kind of loan contract, or several contracts, with financial institutions and if we exclude teenagers and pensioners from the reference population, this number will increase even more. The average number of loan contracts per person4 in commercial banks also seems to be quite high.

Improved access to finance and rapidly increasing number of adults with debt in different financial institutions are reflected in various macroeconomic indicators commonly employed to measure indebtedness of the population. For instance, the highest household debt to GDP ratio before the global financial crisis of 2008 was below 15%, while this indicator reached a historic high of 35% at the end of 2016. From this we can conclude that debt accumulation in the economy is increasing much faster than Gross Domestic Product.

Even more alarmingly, household debt to households’ disposable income ratio skyrocketed to 200%. Such a high ratio is rare in the world. For example, there were only 5 countries among OECD nations in 2015 that had the ratio higher than Georgia – Switzerland (211%), Australia (212%), Norway (222%), Netherland (277%) and Denmark (292%). The same measure was relatively low (commonly less than 100%) for less developed countries5.

No doubt, debt to disposable income is a very simple measure, and policy makers should be cautions when interpreting it. For example, this ratio compares the stock of debt to the flow of disposable income and a person – it doesn’t mean that a person is required to pay off their loan in a single year. Moreover, debt to disposable income ratio measures debt of people who borrowed money relative to the income streams of people who may or may not have borrowed6.

To better see the dynamics of debt burden, one could look at the ratio of household debt service and principal payments to income. It is not surprising that the average debt burden of Georgia was relatively low in 2012 and its growth accelerated only in the beginning of 2015, reaching the peak value of 24.6% in the third quarter of 2016.

This recent worthening of the debt burden is directly related to the sharp depreciation of lari against the US dollar and slowdown in economic growth.

And yet, despite the increasing burden of debt households seem to be repaying their loans: both by IMF and NBG measures, the non-performing loans of deposit taking institutions remain at reasonably low level (it is widely recognized that non-performing loans are much higher in case of microfinance institutions, but it creates less problems in terms of financial stability). Thus, the stability of deposit-taking financial institutions is not yet under threat.

Just because non-performing loans ratio is low and stable, it doesn’t mean that we have nothing to worry about. Elevated debt levels create the risk of lower consumption and sluggish GDP growth that further increase the risk of over-indebtedness in the future.

In the economic literature, over-indebtedness is defined as inability to meet a recurring expenses associated with the contracted financial commitments (this inability must be persistent to exclude one-off occurrences like forgetfulness). Society with excess borrowing is prone to over-indebtedness when 'risky life events' take place. For example, a sudden job loss (quite relevant when economic growth has slowed down), a business failure, illness and emergency surgery treatment (despite universal insurance system, patients still need to share expenses) and sharp currency depreciation (especially for countries with huge currency mismatch).

Furthermore, over-indebtedness might be caused by irrational borrowing by individuals which comes from poor financial management skills of the population and aggressive marketing by lenders, which endangers the least educated and the least well-off groups of the population.

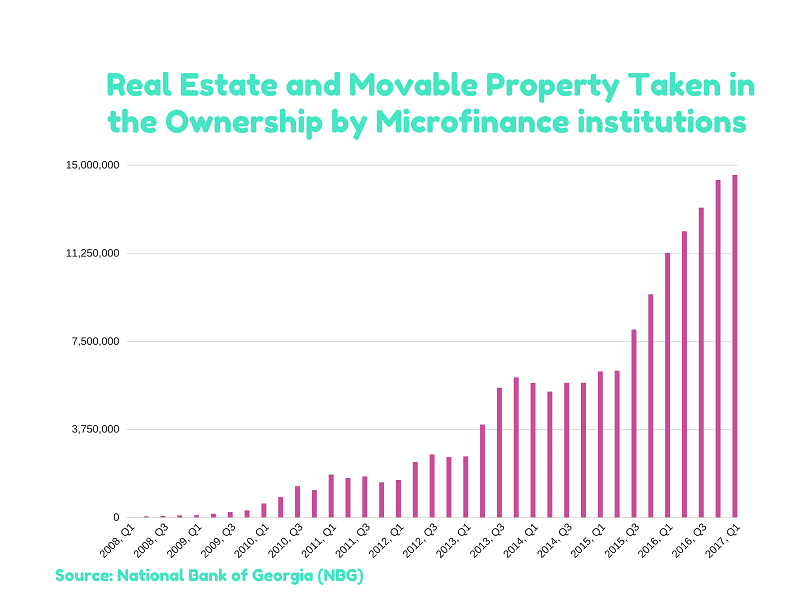

Going back to the story told in the beginning of the blog, over-indebtedness is especially painful when people lose their property. In this respect, the lending practices of microfinance institutions (MFIs) call for further scrutiny.

It is widely accepted that most MFIs get their high profit from charging high interest rates, and from repossession and sale of the pledged real estate in case of a default. Since the collateral requirements are very high relative to the value of the loan, even if the MFI sells an expropriated property at half a price, they can still profit from a loan project.

Therefore, there is a strong issue of moral hazard – MFIs are mainly ignoring financial health of borrowers (they even give loans to the people without permanent income) and rely on the real estate provided as a collateral. Bearing in mind the much stricter loan standards in commercial banks, the MFI type of credit is mainly taken by poor and unemployed people. They are the ones most vulnerable to over-indebtedness trap (Economic Policy Research Center (EPAC) – Management of nonperforming loans in Georgia, 2014).

These findings perfectly agree with the empirical data. First, the number of loan contracts with microfinance institutions has been increasing dramatically in the past several years. For example, in the first quarter of 2013 there were 400 000 loan contracts with microfinance institutions, while this measure increased to 700 000 by the first quarter of 2016 and then reached a historical high of 1.1 million in the last quarter of the same year.

Second, according to the Financial Access Survey (FAS) of the International Monetary Fund, Georgia was the third country by the number of borrowers from microfinance institutions per 1000 adults in 2015, behind Bangladesh and Peru.

Third, the amount of real estate and movable property taken into ownership by microfinance institutions has been increasing rapidly in recent years. For instance, the value of repossessed real estate was 1.6 million GEL in the first quarter of 2012, then it increased to the 6 million GEL in the first quarter of 2015 and skyrocketed to the historically high 14 million GEL in the first quarter of 2017 (see the graph above). Therefore, despite the fact that MFIs are, for the most part, not deposit taking institutions, we should remember that behind these “impressive” numbers, there are stories of poor and vulnerable people whose finances collapsed under burden of expensive loans and who lost the only property they owned.

1 Source: Economic Policy Research Center (EPAC) – Management of nonperforming loans in Georgia, 2014.

2 Number of borrowers from commercial banks per 1000 adults (Financial Access Survey (FCA)) covered 54 developed and developing countries. Turkey is the leader among these countries with 774 borrowers per 1000 adults. Furthermore, there is no information provided by IMF related to the same measure for Armenia and Russia. Azerbaijan is only 20th in the global ranking with only 285 borrowers of the commercial banks per 1000 adults. http://data.imf.org/?sk=E5DCAB7E-A5CA-4892-A6EA-598B5463A34C&sId=1390030341854

3 It is worth mentioning that some of these loans are already payed off, but are still among registered loans.

4 According to the Financial Access Survey (FAS) of International Monetary Fund (IMF) Georgians had 1,018.22 loan accounts with commercial banks per 1000 adults in 2016. This indicator has been rapidly increasing over the last several years. For example, the number of loan accounts with commercial banks per 1000 adults was only 577.7 in 2012. This measure is much higher for microfinance institutions.

5 OECD Database: https://data.oecd.org/hha/household-debt.htm

6 Justin Kuepper, What is the Debt-to-GDP Ratio?, 2017