30

June

2022

30

June

2022

ISET Economist Blog

Monday,

21

May,

2018

Monday,

21

May,

2018

Monday,

21

May,

2018

Monday,

21

May,

2018

That there is a persistent demand for adult education should come as no surprise. Most people would agree that learning is a lifelong process. A distinction, however, should be made between the notion of learning understood as a process of self-discovery over one’s lifetime and learning understood in terms of the acquisition of a certain set of skills, often for the purpose of advancing one’s position in the labor market. The two notions, although distinct, are related. It can be argued, for example, that the more skills we have, the more we can engage with other people, which also contributes to our life experience. The opposite is also true. The more we learn about ourselves through life experience, the better we are able to tell what skills we lack or can improve on, which can serve us and others well in life.

It is also possible that there is some hindering point of skill acquisition at which a relative surplus of skills starts to accumulate, which is seemingly beyond what is necessary for regular task performance. This may in part explain age discrimination in the labor market. With age (that is, with life experience) people are perceived as acquiring more non-marketable skills while falling behind in the speed of simple task completion. It can be argued, for example, that with experience (with age), people will care more about the quality of their work. While on the one hand, performance speed increases with repetition or mastery of a task, the insistence on quality improvement, which is infinite in its possibilities and, as such, crucial and necessary in our development as persons, will on the surface tend to slow down a particular activity. As a result, there may be a natural progression into seemingly taking more time to do things.

There surely are other reasons which affect productivity. Productivity can be understood as essentially being about communication, that is, about how effectively we relate our know-how to others. Understood this way, communication is then related to our level of socialization. Any decreased socialization (due to long-term unemployment, shorter or longer periods of under-employment or unemployment due to illness, family leave, etc.) is thus likely to additionally decrease initial productivity once back in the workplace. Understanding the role communication plays can help us adapt the work training and/or adult education programs in a way that will make them more effective for labor market purposes.

To the extent that adult education influences a larger issue of unemployment, it should be of particular interest to policymakers. While there is evidence of long-term unemployment in well-performing economies as well, their effects are particularly felt in the lower-income countries and the so-called “transitional” economies, in particular given the lack of other sorts of social protections due to general economic hardship.

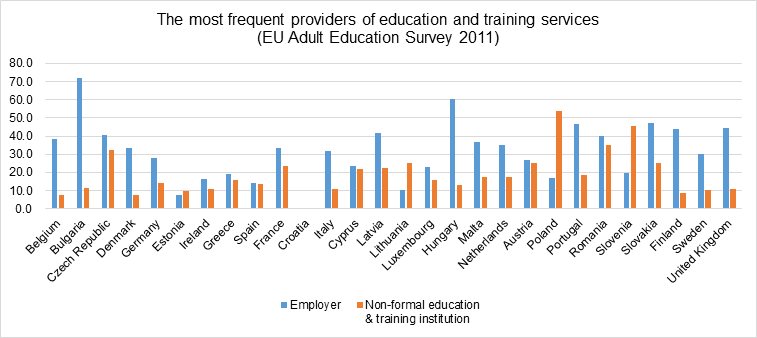

The EU Adult Education Survey provides some useful insights into the kinds of trainings adults tend to receive. Perhaps most relevant for this discussion is that the great majority of adult instruction and training in countries across the EU was provided by employers. This suggests that the greatest access to continuing education is to be had by already-employed people, and not those who arguably have greater need of skill maintenance and acquisition – the unemployed. The skill gap between the employed and the unemployed thus is ever-increasing, making it more difficult for the unemployed to compete for whatever available positions there are.

Another interesting observation is that more men than women took part in job-related, non-formal instruction (84.8% to 75.5%); women participated more in non-job-related, non-formal training than men did (24 % to 14.5%). What may call for a closer look is that the financial support for job-related non-formal instruction provided by employers was also higher for men than for women (76.6% to 64.9%). On one hand, this may suggest a somewhat unequal treatment of men and women in the workplace. On the other hand, the relatively higher percentage of women seeking non-job-related training may suggest a greater need on the part of women to explore a variety of interests.

The lessons from the EU could serve other countries well. The unemployment challenges in Georgia make educational policy considerations particularly relevant. While there is no official data on adult informal education, there have been programs in recent years aimed at addressing the issue. Any potential educational policy, however, should aim to preserve that which is unique to Georgian culture, society, and the economy as well. Going back to the discussion above, if the level of skill and socialization (communication) plays an essential part in employment outcomes, and if in fact, employers are those who provide most of the job-related trainings (as we saw in the EU data), perhaps a policy should aim at not only providing educational programs that directly maintain and train on job-related skills, but also those that seek ways to put people together in interactive ways that increase communication and socialization, which would open avenues for speedier reintegration into or perseverance in the labor force. A dance class, for example, could perhaps do just that.