30

June

2022

30

June

2022

ISET Economist Blog

Monday,

18

June,

2018

Monday,

18

June,

2018

Monday,

18

June,

2018

Monday,

18

June,

2018

Georgian and Armenian ruling parties have been until recently basking in the glory of high GDP growth rates. Armenia’s stellar growth performance of 7.5% in 2017 and Georgia’s respectable 5% are, indeed, worthy of praise. However, do these figures really matter for the objective well-being of the majority of Georgians and Armenians? Second, how does economic growth, as measured by GDP, affect people’s subjective perception of happiness? Third, what does it do to crime rates and people’s appetite for political representation, social justice, and fairness?

A belief traditionally held by liberal economic thinkers and ideologues is that wealth tends to ‘trickle down’ from the upper echelons of society to the lower classes. The implication of this trickle-down proposition is that economic growth benefits everybody by increasing the overall size of the pie. Yes, the entrepreneurial class may be the first to benefit from expanded business opportunities, but more business (and businesses) also means more jobs, and more income redistributed to the poor – directly, through taxes and social transfers, and indirectly, through better-financed public education and healthcare systems. Economic growth thus helps reduce the absolute level of poverty in a society.

The ‘trickle-down’ theory makes a lot of sense … in theory. Whether it actually works in practice depends on a few important nuances. First, if economic growth is generated in just a few capital-intensive sectors of the economy, such as Azerbaijan’s oil and gas sector, it is likely to create relatively few jobs. Moreover, these new jobs may not be suitable for the uneducated and unskilled urban and rural poor. Second, economic growth certainly increases the amount of taxable income in an economy, but whether and when the extra tax revenues will benefit the poor depends on a country’s political priorities. At one extreme, the government may choose to increase social pensions; at another, it may increase public spending on defense or reduce the tax rate on businesses (so as to encourage investment and future growth).

At least for a while, Georgia’s economic growth has been accompanied by a reduction in extreme poverty. First, Georgia’s economic growth in 2013-14 was primarily driven by labor-intensive sectors – tourism, trade, and traditional agriculture. Second, and even more importantly for poverty reduction, since early 2013, Georgia has been actively implementing a wide range of redistribution policies – from universal healthcare coverage and free preschool education to increased targeted social assistance (TSA) and pensions.

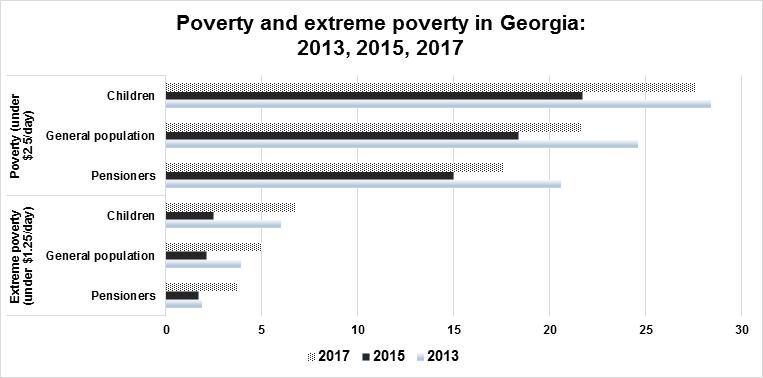

In more recent years, however, social benefits did not keep up with inflation, erasing earlier gains in the battle against poverty. Using consumption expenditure data, UNICEF assesses that the share of the general population below the extreme poverty line (consuming below the 1.25 USD per day threshold) more than doubled in 2015-2017, from 2.1 to 5%. Particularly worrying is the sharp increase in the share of children growing in extreme poverty – from 2.5% to 6.8%.

Thus, at least in Georgia’s case, economic growth failed to trickle down in a sustained fashion, resulting not only in higher absolute poverty but also in a growing sense of unhappiness and frustration with the country’s economic and political direction.

There is a fairly broad consensus in the social science literature, as discussed in a recent CityLab piece, that even when some of the wealth created in the process of economic growth does trickle down, money alone does not make people happy. For example, a study by Shigehiro Oishi (University of Virginia) and Selin Kesebir (London Business School) finds that happiness (“subjective well-being”) in 16 developed countries is correlated positively with GDP per capita and negatively with income inequality (measured by the Gini coefficient). Much more surprisingly, when looking at 18 less-developed Latin American economies, Oishi and Kesebir find that not only inequality tends to dampen happiness, but – in contrast to advanced nations, – happiness does not increase alongside economic growth.

What can explain the fact that economic growth cannot buy happiness in the less-developed Latin American nations? One reason may be the very high initial levels of inequality in Latin American societies, and the failure of their political systems to make sure that a fair share of newly created wealth trickles down fast enough to the poor masses.

When it comes to income inequality, Georgia and Armenia do more or less fine relative to their level of development. As reported by the World Bank, the level of income inequality in Georgia and Armenia (Gini coefficients of 38.5 and 32.4 in 2015, respectively) is much lower than in African, Asian, and Latin American societies divided by caste, clan, and race (the most unequal societies, such as the South African Republic and Haiti, have Gini coefficients above 60). As could be expected, however, Georgia and Armenia are quite a bit less equal than some of the wealthiest and most egalitarian societies of the world, such as Finland and Iceland, with Gini coefficients around 25.

However, what is important in the context of subjective well-being and happiness is not the absolute degree of income inequality, but how people in a society feel about it. For one, people’s perceptions of existing social and economic disparities may be determined by cultural factors (one may argue that Nordic people tend to place a higher value on social solidarity, whereas caste-based societies tend to accept inequality as a given, reflecting the will of God). Additionally, perceptions are affected by the speed with which social gaps are closed (or not) through the political system. Stagnation or slow progress in addressing social disparities is likely to generate frustration, desperation, anti-social or radical political behaviors, as we have recently observed in both Georgia and Armenia.

For all their differences, Georgians and Armenians share much in common. Both are small ancient nations that survived through centuries of imperial domination and conquest. Both proudly embraced independence 100 years ago and, again, in the early 1990s. And both are seriously unhappy with the current state of their political institutions.

Out of 156 countries included in UN’s World Happiness Report 2018, Georgia and Armenia have been ranked 128th and 129th, only a few notches ahead of war-and-corruption torn Ukraine (138th) and not very far from Africa’s failed states at the very bottom of the ranking: Burundi, Central African Republic, South Sudan, Tanzania, Yemen, and Rwanda. Not surprisingly, the happiest five nations in the world are those that place social harmony and fairness on par with individual success: Finland; Norway, Denmark, Iceland, and Switzerland.

Importantly, unhappiness and readiness to act are strongly related to a perceived lack of social justice. It is not so much about being poor, but the fact that government ministers are driven around in very nice cars that you will never be able to afford; the fact that your children will never have the chance to acquire a decent education; the fact that the guy next door is somehow above the law or is able to get special treatment from the courts, the law enforcement agencies, and the political system.

Societies undoubtedly differ in the degree of social injustice they can acquiesce without putting up organized resistance. And if there is something the Georgian and Armenian people really share in common it is the very little degree of patience they have for their rulers. Judging by recent events in both countries, the two people have clearly had enough.

Armenian people’s success in bringing down a corrupt regime is truly inspiring. An unprecedented wave of solidarity swept through the entire society, manifesting itself in civil disobedience acts and protests cutting across Armenia’s geography and social classes. Restoring social solidarity appears to be at the top of Nikol Pashinyan’s priorities and his vision for Armenia’s Velvet Revolution: “healthier institutions, less corruption, fair pay, stronger regulation, better education, advancement for all.”

The eagerness with which thousands of people have been gathering in Tbilisi’s Rustaveli Avenue to protest perceived injustices suggests that Georgia’s “deplorables” and “desperados” have also reached a point of no return.

Unlike Armenia, corruption may not be Georgia’s main concern. However, the Georgian people appear to be fed up with being ruled by dominant parties and powerful individuals enjoying a near-monopolistic status in the country’s political arena. This objective weakness of Georgia’s political system and the country’s fundamental inability to address persistent social gaps appear to be at the root of the current crisis.

* * *

Giorgi Kvirikashvili was one of the finest prime ministers in Georgia’s modern history, and his departure will not help tackle any of Georgia’s challenges. If anything, the manner in which Kvirikashvili was thrown under the bus serves to illustrate Georgia’s weakness as a democratic polity and the urgent need for political and economic reforms going beyond PR and the quick ease-of-doing-business fixes.