02

July

2024

02

July

2024

ISET Economist Blog

Friday,

09

December,

2011

Friday,

09

December,

2011

Friday,

09

December,

2011

Friday,

09

December,

2011

Twenty years ago, on 26 December 1991, USSR broke into 15 pieces, 15 independent states. Amid great hopes, each of these states embarked on a path of transition: from socialism, from the one-party state system, from the relative security of a small city apartment, a dacha, and a Lada to… an uncertain future.

For the small Baltic pieces of the USSR puzzle, this road led to EU membership and all of the associated goodies. For many others, however, this may have been a “transition from nowhere to no place” (see the eponymous 2004 bestseller by my number one contemporary fiction writer Victor Pelevin. (In Russian: Диалектика Переходного Периода (из Ниоткуда в Никуда)).

One way to come to this sobering conclusion is to look at the extent to which “democracy” has taken root in the former USSR space. This can be done, for instance, by looking at the so-called “democracy index” compiled by The Economist. According to this index, not a single former Soviet republic progressed to “full democracy” by 2010, though the three Baltic states are getting close – topping the list of “flawed democracies”. Moldova and Ukraine are close to the bottom of the “flawed democracies” list, squeezed in between Mongolia and Namibia. The other 10 are classified as either “hybrid regimes” or outright “autocracies”.

An economist might want to analyze the progress of democracy through the prism of competition policy. After all, democratic governance is often justified as a framework for the free competition of ideas (this is the true essence of democratic politics, which we all love to hate). A political system can be analyzed as a market in which parties compete over peoples’ votes. And just like in any market, we may find that different political systems exhibit different degrees of competitiveness.

The more competitive a political system, the more likely it is to produce optimal outcomes (collective choices). Just like in economics, competition implies greater responsiveness to popular demand, better “service”, product innovation, meritocratic hiring, and promotion policies.

A rather popular measure of economic competition among firms is the so-called Herfindahl–Hirschman Index, or HHI). It is defined as the sum of the squares of firms’ market shares (expressed as fractions) within an industry.

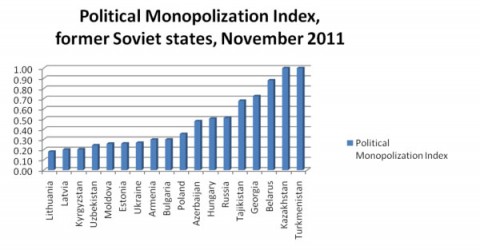

To measure the extent of democratic transition for the ex-Soviet states, we calculated a version of the HHI index which we call HH Political Monopolization Index (HH-PMI). Instead of market shares, HH-PMI uses the shares of seats held by political parties in the national parliaments. It takes the value of 1 for single-party “democracies” and a relatively low value (but certainly not 0) for parliaments populated by many parties of roughly equal size. To provide a benchmark, we added a few randomly selected Eastern European countries. The results are as follows:

This index does not provide an accurate picture of the true state of democratic transition. In particular, it flatters such “democracies” as Uzbekistan and Russia, where a semblance of political competition is carefully maintained by the ruling elites through the creation of “pet party projects “(PPP). See the recent scandal involving the Kremlin puppeteers, the Pravoe Delo (Right Cause) PPP, and Mikhail Prokhorov.

Former USSR countries are not doomed to fail as democracies. To the extent their citizens retained any freedom of choice, they can choose differently - by using the ballot box, or by taking their cause to the streets.