02

July

2024

02

July

2024

ISET Economist Blog

Sunday,

18

December,

2011

Sunday,

18

December,

2011

Far from being the root of all evil, money is one of the most spectacularly useful human inventions. On par with the technology of a wheel, the technology of money has made civilization as we know it possible. But what kind of technology does money replace?

Narayana Kocherlakota (JET 1998) argues that money is a form of memory. Here is an example: John has apples and wants bananas. Mary has oranges and wants apples. Paul has bananas but wants oranges. When John and Mary meet, John can accept money from Mary in exchange for apples and use this money to buy bananas from Paul. Alternatively, however, John can give Mary a gift of apples. If the gift is made, Paul will give John bananas in the future (and be able to receive a gift of oranges from Mary). If the gifts are not exchanged, everyone stays with what they had before.

Viewed in this way, monetary exchange is nothing but an intricate web of gifts. Money is just a way of “remembering” the past deeds – a way for Mary to let Paul know that John has fulfilled his side of the bargain by giving her a gift in the past.

And so, throughout our working lives, we accumulate the tokens of memory. Hoping that in the future, when we are no longer able to work, these tokens will remind people of how much they valued the things we did for them in past and will reward us in return.

Surely, this hope may not always be fulfilled. Hyperinflation is one example of such a break of trust, a form of collective amnesia, when the society no longer remembers the past. In one of the worst cases, Hungary in 1946, the memory slates were being wiped in half approximately every 16 hours.

The stores of value, other than paper money, exist, of course. Gold, jewelry, houses, and even skills we acquire over a lifetime are used for that purpose. But these things too hold only as much value as the people around us are willing to attach to them - at the moment of time we need to make the exchange.

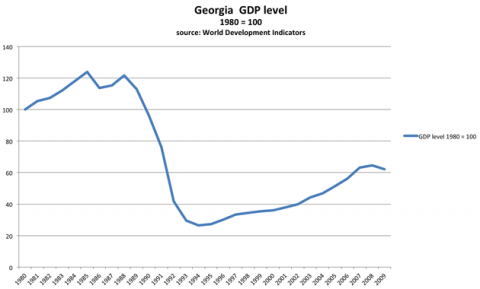

The graph below shows the output collapse in the Republic of Georgia in the 1990s. People lost life savings throughout the Soviet Union. But more than that – all of a sudden like in a fairytale gone wrong, a mathematician turned into a taxi driver and a physicist sold second hand clothes on the street.

On the individual level, this would be equivalent to waking up one morning to find that you have lost your place in the community, the friends you trusted, the knowledge and skills you have accumulated throughout your life. Such cataclysms are rare, but once they happen, they affect people profoundly. It may take more than one lifetime to re-establish society. And both individually and collectively it may take us a while to do the same or better than we once had.

So what is the best store of value? I’m afraid I don’t have a good answer to that. Perhaps the examples of economic cataclysms can remind us of the importance of good institutions. With the severe malfunction of the institutional frameworks, even the very important skills can become suddenly useless, and even the best of people will lose their memory.