30

June

2022

30

June

2022

ISET Economist Blog

Wednesday,

21

December,

2011

Wednesday,

21

December,

2011

One of the definitions of a safety net that one can find on the internet is the following: “a net placed to catch an acrobat or similar performer in case of a fall”. This brings to my mind images of thrilling performances I saw at the circus when I was a child. I have to admit in most cases a safety net was used. It was only removed on some rare occasions, and the increased tension became palpable. We knew that only the best acrobats could dare perform in those conditions because even a slight mistake or distraction could lead to disastrous consequences.

Born in this context, the term safety net has soon been extended beyond circuses. The same internet source, right below the standard definition adds: “fig. a safeguard against possible hardship or adversity: a safety net for workers who lose their jobs”.

Imagine you are a European worker in a time of crisis. You are the only breadwinner in your family and you become unemployed. Your families situation is going to worsen significantly, but you know that – at least for some time - you and your family will be able to survive thanks to your unemployment benefits and to other forms of social support. In the meantime, hopefully, you will be able to get a new job – maybe thanks to the help of a public employment agency - or will at least be admitted into some publicly sponsored training program increasing your probability to get back to work.

Imagine that, instead of being fired, you get sick. Luckily most of the costs for your care will be covered by the public healthcare system. You will continue receiving your salary (with a reduction as the length of the period of sickness goes beyond a certain number of days) for at least a few months, typically until you can go back to work. If your sickness is really serious, at some point you will not receive compensation but you will keep your job unless you stay away from your workplace continuously for a very long period. Should you lose your job, you will still be able to rely, for a while, on unemployment benefits and on additional forms of social support. Your family will be suffering of course, but at least you will be able to “gain some time” to try finding a solution.

Now imagine a different scenario.

You lose your job. You get one month severance pay but no unemployment benefits. The labor market is hardly creating new jobs, so you have a high probability of not finding a good job and will have to either accept being unemployed for a long period of time or to work in badly paid temporary jobs, maybe in very dangerous working places (because nobody is in charge of checking working conditions). In case you choose not to take the risk, and to try looking for safer jobs, most likely during your unemployment period you will not receive any training and certainly no support from (non-existing) public employment agencies.

What if you are sick? All the healthcare costs fall on you. If you have private health insurance, you get some assistance. If not, you have to use your savings in order to get some treatment. You receive one month's worth of salary, after which your employer is free to fire you without having to give you any compensation. So you suddenly find yourself sick and not only unable to help your family but being a burden to them, with no public support and no income. To be fair, you might receive some sort of assistance, after you have applied to the government for support as a needy household if your situation has deteriorated so much that you cannot ensure even your subsistence (maybe by selling assets). But don’t expect the support to be that high.

The picture looks much different, doesn’t it?

This second case is not that of a fictional country. It is just a representation of the conditions of most workers in Georgia.

If you keep this in mind, you will not be surprised when looking at the following pictures taken from the latest EBRD (European Bank for Reconstruction and Development) Transition Report, titled: “Crisis and Transition: the People’s Perspective”. The tables and pictures included in the report are based on a series of household surveys conducted by EBRD in a number of transition countries plus a few selected countries of Western Europe. The aim of this study was to study how the crisis had affected households’ welfare in order to draw some conclusions about the potential vulnerability of countries and households to future crises.

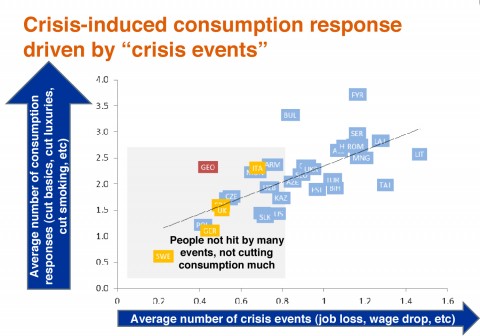

In this first graph, Georgia (in red) stands out quite a bit above the regression line. This is defined as an “outlier”. In this case, being an outlier means that Georgian households, despite having been themselves hit by a relatively small number of negative events, appear to have suffered much more than households in similar situations in other countries. In other words, they were forced to cut their consumption much more than households in other countries.

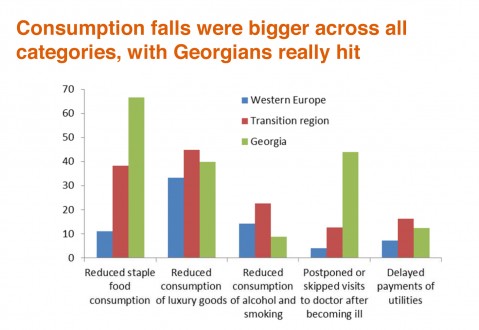

The second graph (below) allows us to see where Georgian households had to cut their consumption. Of course, cutting the consumption of luxury goods is not the same as cutting on food or healthcare. Looking at the second picture, if possible, makes things look even worse. Most households had to cut exactly where one would hope they would not have to: staple food consumption and visits to doctors.

Neither of these cuts bode well for future Georgian households, as they are likely to have long-lasting (negative) effects on them. Especially as a new world crisis seems to be approaching.

Why this discussion about Georgia and safety nets? Because for some time now Georgia has been presented consistently as a showcase country with an impressive reform track (including an extremely liberal labor market reform that has drastically reduced all forms of workers’ protection) and equally impressive growth rates.

Much less has been said about how Georgian people have been affected by these reforms. For sure the picture that emerges from the EBRD study is of a country where households are extremely vulnerable to any slowing down of the economy or worsening of the macroeconomic conditions. Much more than in most other countries.

Again, looking at the EBRD study, we can see that this is related to at least two factors: on one hand, the extremely weak safety net provided by the state; on the other hand, the limited success (so far) in translating high growth rates into a substantial amount of new, “good quality” jobs.

This is what led the EBRD, after presenting these results to suggest the following two key priorities for the Georgian government.

“…to create a basis for export-led growth… […] but also to establish an effective social safety net”.

I would like to conclude with my personal answer to the question: “who needs a safety net?”

A lot of people, I would say, especially in times of crisis like these ones. After all, even the best acrobats would not dare perform all the time without it, especially when they are trying their most dangerous performances for the first time and when preconditions are less than perfect. Why? Because the cost of failure would be too high.

Like in the case of acrobats – even more, as they are not risking their lives only – policymakers have the responsibility of taking into account in their evaluations what could go wrong and thinking of ways to minimize negative impacts on the population.

Most economists would agree that only a sustainable increase in the welfare of citizens (including the most vulnerable ones) is the true sign of the development of a country in the long run. Assuring this, as someone sometimes seems to forget, requires also creating and maintaining – especially when markets are less than perfect, a solid social safety net.