30

June

2022

30

June

2022

ISET Economist Blog

Tuesday,

09

April,

2013

Tuesday,

09

April,

2013

Large gaps exist between male and female wages across the world. Eurostat data about the unadjusted Gender Pay Gap (GPG) represent the difference between average gross hourly earnings of male and female paid employees as a percentage of average gross hourly earnings of male paid employees. In 2011, in the EU, women earned 16.2 percent less per hour compared to men. The difference varies from 2.3% for Slovenia to 27.3 % for Estonia. The Worldbank Development Report on Gender Equality analyzed data of sixty-four developing and developed countries around the world and found the earnings gap between males and females with the same characteristics to be within the range between 8% and 48% of average hourly females' earnings. The gap was found to be more pronounced in low-income countries.

The available Georgian data tell a similar story. According to the National Statistic Office - in 2012 - for each 1 GEL of average nominal monthly salary earned by men women received 58 Tetri. Even taking into account the fact that women are usually working a lower number of hours than men, this huge wage gap in salaries is an indication of an existing gap in hourly wages too.

Why is there a gender pay gap? Many would-be quick to answer: it is because of gender discrimination (and probably suggest tougher anti-discrimination legislation)!

This, however, is far from obvious. Even if, controlling for demographic characteristics (age, region (urban/rural), education, marital status, and presence of children) and job characteristics (hours of work per week, employment status, occupation, economic sector, and formal/informal nature of the job) much of the earnings gaps remain unexplained, suggesting that the gap could be also due to other characteristics we are not yet taking into account. Among other causes that could explain the existence and the persistence of a gender pay gap particularly interesting are the differences in individual lifestyle preferences.

Preference theory, a multidisciplinary (mainly sociological) theory developed by British sociologist Catherine Hakim, postulates that women’s expressed preferences are better predictors of their employment status than their education levels. She argues that preference theory largely explains the persistence of sex differentials in labor markets and also the gender pay gap. Women would tend to favor quality of life and job satisfaction over higher earnings. In support of this theory, the economist Arnaud Chevalier from the University of London surveyed more than 10000 people in the UK and found that men are more likely to state that career development and financial rewards are very important, and to define themselves as very ambitious, while women emphasize job satisfaction, being valued by employers and doing a socially useful job. Two-thirds of women in this sample expect to take career breaks for family reasons; 40 percent of men expect their partners to do this, but only 12 percent expect to do it themselves.

Individual lifestyle preferences are likely to play an even greater role in Georgia due to our predefined attitude towards gender roles and their consequences. Georgia is a unique country, characterized by a distinct mix of western and eastern values. Women are raised in a patriarchal society, where gender roles are predefined and deeply engraved from childhood. Most Georgian girls grow up hearing the following statements: “you cannot stand alone”, “you are too fragile”, “you are in need of protection”, and so on. As a woman you feel that the main determinant of your personal success in this society is not having a successful career; rather it is your marital status and, more specifically, fulfilling your obligations as a woman, as a housewife, and as a mother.

These social factors increase the likelihood that Georgian women “develop” the so-called Cinderella syndrome, related to Catherine Hakim’s theory explaining the gender pay gap. The Cinderella syndrome describes a women's fear of independence, and her unconscious desire to be taken care of by others (men). This alleged syndrome was first described by Colette Dowling in her 1981 book The Cinderella Complex: Women's Hidden Fear of Independence. This - mainly psychological - factor is usually not accounted for by economic analyses of the gender pay gap, although it probably should. In particular for analyzing wage differentials in traditional countries like Georgia, psychological factors might subconsciously affect women’s labor supply, their reservation wages, and even their performance at work (especially when competing with men), ultimately resulting in larger pay gaps.

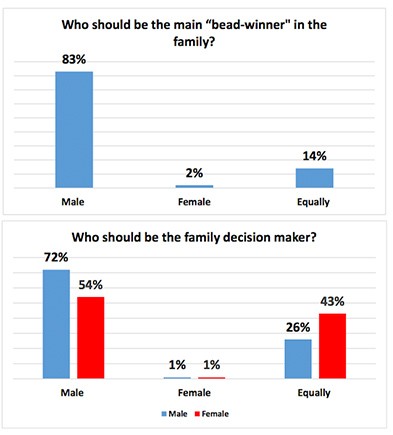

A survey on gender issues based on telephone interviews, carried out in Georgia in 2012 by the Center for Social Science, provides support for the possible existence of the Cinderella syndrome in Georgia. The survey shows that a large part of the interviewed believes that men should be the ones who are the family's decision-makers and that they should also be the main “bread-winners”. 83% of respondents think that men should be the main breadwinners in the family and 63% believe that they should also be the family’s decision-makers. It is interesting to note that more than half (54%) of women agree that men should be family decision-makers. In addition, 92% of respondents think that the most appropriate age for getting married for women is 18-25 years old. As 18-25 is the age in which individuals are acquiring human capital and skills for their future careers, it is not unreasonable to expect that, if this time period is used for childbearing and rearing, it can result in women possessing a lower level of skill and consequently receiving lower earnings.

There is a gender pay gap between males and females in Georgia and it appears to be large. Discrimination might explain part of it but it is certainly not the only cause. Differences in attitudes, cultural background, and psychology, affecting lifestyle choices, are also likely to play a major role in this. Instead of using discrimination as a scapegoat on which to blame the existence of a gender pay gap and consider it as evidence of a problem one should get rid of at all costs, it would probably be better to look at things in a more differentiated way. What if important factors for the current state are to be found in females’ own choices? What if individual and social preferences were driving what we observe in the labor market? Would the existence of a gender pay gap really constitute a problem then?

As long as there are no external effects involved and individuals are fully aware of the implications of the choices they make, the best course of action might be to let everyone decide what is best for her. Even continuing to look for the Prince Charming, if one feels so.