02

July

2024

02

July

2024

ISET Economist Blog

Saturday,

04

February,

2017

Saturday,

04

February,

2017

Saturday,

04

February,

2017

Saturday,

04

February,

2017

Unofficial (partial) dollarization describes a situation when a foreign currency is used alongside the domestic currency for transactions purposes and as a store value. High partial dollarization is not good for a country, as it ties the hands of its Central Bank when it wants to use monetary policy. In a highly dollarized economy, national currency depreciation can even lead to financial instability.

As a transition economy, Georgia is characterized by high levels of dollarization. Therefore, recent waves of lari depreciation have prompted authorities to step up their efforts to achieve sustained de-dollarization of the economy. To do this, the Georgian government, together with the National Bank of Georgia, has drafted the so-called “Larization Plan.”

Despite the fact that many of the policy measures in the current Larization Plan are widely recognized as effective tools against high dollarization (we will not mention all of them in this blog), there are questions related to the two most controversial points in the de-dollarization strategy: voluntary conversion1 of foreign currency mortgage loans to the domestic currency; and mandatory issuance of small loans2 in local currency only. These two initiatives will most likely create considerable mismatches in the banks’ balance sheets, as the asset side of the banks’ balances (credits) will be rapidly de-dollarized, while dollarization of the liability side (deposits) will remain relatively high.

Some policymakers believe that converting foreign currency loans will stabilize the lari exchange rate against the dollar. The logic is as follows: private borrowers in Georgia, who previously had to convert their lari into USD to pay back loans (driving up the demand for USD), will now simply pay in lari. Problem solved? Perhaps not. We have to remember that it will be banks who will be converting lari into USD to pay back interest on their dollarized liabilities. In both cases, the international reserves of the National Bank of Georgia may need to be tapped to keep the lari exchange rate stable against the USD.

It is worth mentioning that de-dollarization by forced administrative means always entails a risk of negative spillover effects to other parts of the economic system. For example, banning small loans in foreign currency might lead to an increase in interest rates on lari loans, and further impede sustainable economic growth (banks will try to attract deposits in lari, which might increase interest rates on lari deposits and increase interest rates on lari loans as well). In addition, strict administrative measures always include the risk of financial disintermediation (a fancy term for people not trusting the banks anymore) and capital flight.

So, what can current policymakers learn from the past experiences (both foreign and domestic) of successful de-dollarization processes?

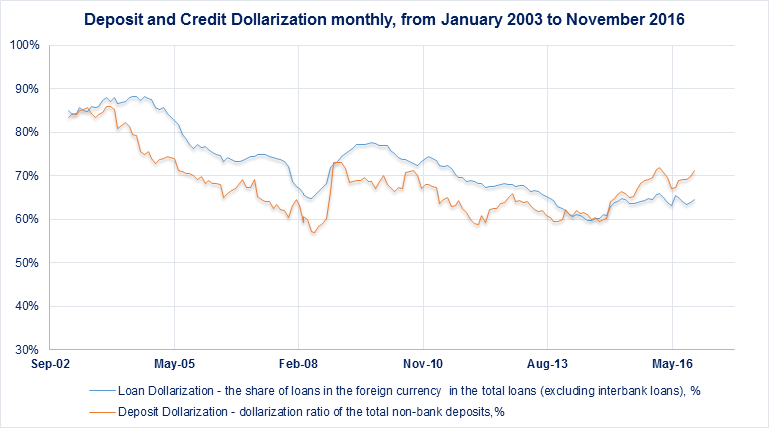

Policymakers often talk about foreign experiences, but it is not frequently mentioned that Georgia already has an experience with successful market-driven de-dollarization. The early years of the post-Soviet transition were full of unsuccessful institutional and structural reforms. A persistent budget deficit led to hyperinflation, sharp currency depreciation, and deteriorated macroeconomic conditions. People started to mistrust domestic currency and financial dollarization reached historically high levels (80-90%). After the Rose Revolution, the newly elected government started to implement ambitious reforms. These reforms, coupled with favorable economic conditions in the region, helped Georgia achieve macroeconomic stability.3 As a result, dollarization indexes were reduced by approximately 20 percentage points. On the chart below we can see that dollarization has been on the decline during “normal” times, increasing only in times of crises (for example, during the global financial crisis of 2008, and during the recent regional economic crisis in 2014-2016).

The main message conveyed by this chart is clear: market forces play an important role in achieving fast, long-lasting de-dollarization. Therefore, countries like Georgia can achieve a lower level of dollarization simply by stabilizing the macroeconomic environment, without resorting to restrictive prudential regulations.

There is a broad range of literature studying the determinants of a successful de-dollarization process. The main message of these studies corroborates the Georgian experience: achieving macroeconomic stability is the main driver of successful de-dollarization. The development of capital markets is also important, while prudential measures are mainly considered to be a supplementary tool to help achieve incremental progress.

While many countries are trying to de-dollarize, only a few of them have fully succeeded in their efforts. For instance, Mecagni and others (2015)4 empirically analyzed a sample of 42 initially dollarized countries, among which 11 countries managed to successfully de-dollarize5, while another 31 countries failed to meet their target. The authors identified key variables that distinguished successful countries from unsuccessful ones. First, they found that the average initial dollarization in successful cases was 67.4%, while this variable was, on average, much smaller in unsuccessful ones – only 48.4%. Second, during the de-dollarization process, successful countries managed to achieve high real GDP growth (on average 2.8 percent higher than unsuccessful ones), improved current account balances (on average by 5.3%), and reduced fiscal deficit (on average, managing to go from a deficit to a small surplus). Finally, successful countries experienced prolonged exchange rate appreciations during the de-dollarization period. However, regression analysis makes it clear that exchange rate appreciation is itself the result of the macroeconomic stabilization, and its pure effect on dollarization is statistically insignificant.

In considering the case studies of successful de-dollarization processes, we see that successful countries share some important characteristics – in all cases, de-dollarization was achieved through macroeconomic stability, supplemented with prudential measures. Peru provides a brilliant example of how market-driven de-dollarization defeats dollarization based on the prudential regulations alone.

In the mid-1980s, the Peruvian government decided to combat dollarization by forcing the conversion of foreign currency deposits to the local currency. This policy turned out to be counter-productive, provoking financial disintermediation and capital flight. The inflation rate reached quadruple digits in the 1990s and the Peruvian sol lost its essential functions. After this painful experiment, government authorities radically changed their de-dollarization strategy. The new plan focused on achieving macroeconomic stability by creating a fiscal surplus, significantly lowering public debt, and stabilizing inflation by introducing an inflation targeting regime, which was followed by significant currency appreciation from 2003-2011. The macro stabilization policy was complemented by prudential regulations to better account for foreign currency risks, and to develop a market for securities with a long maturity in domestic currency.6 As a result, Peru managed to reduce dollarization by approximately 30 percentage points.

All roads lead to macroeconomic stabilization.

To sum up, macroeconomic theory and the analysis of case studies of successful de-dollarization processes suggest that the key contributor to successful de-dollarization is a stable macroeconomic environment. Prudential measures can only be considered supplementary tools. All in all, the most enduring way to reduce dollarization is to achieve – and maintain – macroeconomic stability by keeping inflation low and stable, keeping the exchange rate flexible, improving the country’s current account balance, reversing fiscal deficit (which makes government bonds more attractive and further deepens domestic capital markets), and by conducting structural and institutional reforms that help reach sustainable high economic growth.

1 conversion will take place at the current exchange rate plus a partial subsidy by the central government.

2 loans below 100 thousand lari from January 1, 2017, and 200 thousand lari from January 1, 2018.

3 rapid economic growth, consolidating budget after tax reform, and long-term appreciation of the national currency.

4 Mecagni, M., Corrales, J. S., Dridi, J., Garcia-Verdu, R., Imam, P., Matz, J. . . . Yehoue, E. (2015). Dollarization in Sub-Saharan Africa - Experience and Lessons. IMF Library.

5 Georgia’s market-driven dedollarization in 2003-08 was one of the cases.

6 A similar package was implemented by Israel, Poland, and Bolivia