21

March

2022

21

March

2022

ISET Economist Blog

Monday,

30

October,

2017

Monday,

30

October,

2017

Monday,

30

October,

2017

Monday,

30

October,

2017

On October 21, 2017, Georgia’s entire political map was painted in different shades of blue – the color of the ruling Georgian Dream (GD) party. GD won in all but one race in the country’s municipal elections – achieving solid majorities in all sakrebulo (city councils) and placing party-backed candidates as mayors in all cities and self-governing communities.

Such results are quite unusual, and nearly impossible to achieve nowadays in the politically polarized atmosphere of Western Europe, UK or the U.S. Do they suggest that GD has been exceptionally successful in pleasing the Georgian electorate? The government's supporters would certainly agree with this assessment, citing a myriad of badly needed reforms (ranging from judiciary, to tax administration, to penitentiary systems), the relative calm in Georgian-Russian relations (while staying the course of Euro-Atlantic integration!), and the visa liberalization with the EU.

The opponents (which in the Georgian political landscape are still numerous and vocal) would, however, bring up low economic growth, record lari devaluation, and argue that the Euro-centric foreign policy achievements of GD (like EU visa liberalization or the DCFTA agreement) have sprouted on the ground set by their political predecessors.

Whatever the verdict on GD’s political achievements, it is worth remembering that just a few years ago Georgia’s entire political landscape was painted in different shades of red, the color of GD’s predecessors, the United National Movement (UNM). UNM’s victory in 2008 parliamentary elections was not a smooth sailing. It was achieved against the backdrop of popular protests on the streets of Tbilisi. Yet, it was as overwhelming as GD’s triumphs in 2016 and 2017.

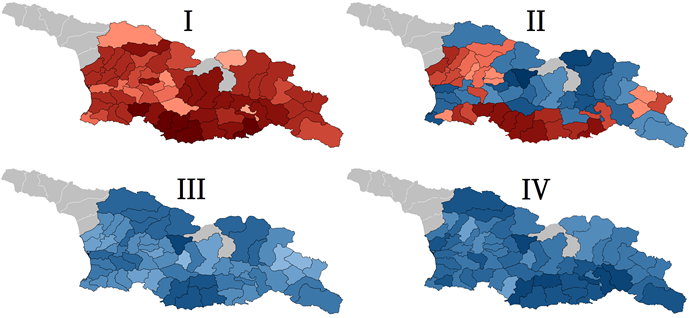

Figure 1. Election results for party list representation in parliamentary elections (2008, 2012, and 2016) and local elections of 2017. A red country turned blue in less than 10 years.

A key explanation (and a major challenge for Georgia’s fledgling democracy) is the predominant tendency of rural Georgians (and ethnic minority voters in particular) to vote for whoever is currently in power.

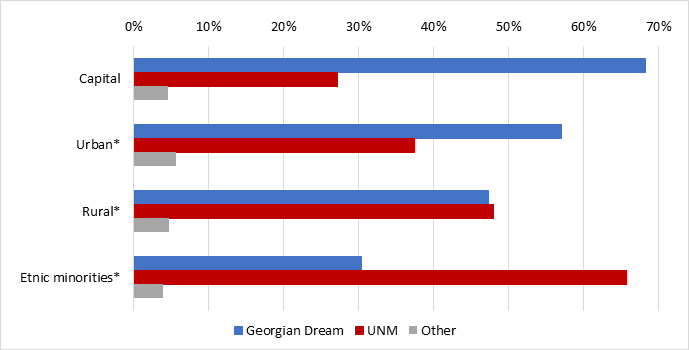

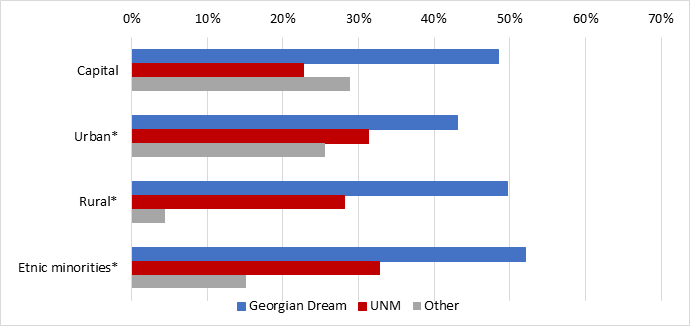

Figures 2(a) and (b) demonstrate the relative ease with which Georgian rural and ethnic minority voters can be swayed to vote for the incumbent administration.

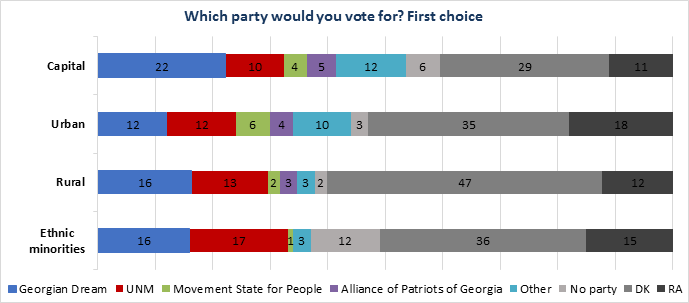

Another very important aspect of political behavior of Georgia’s traditional electorate can be gleaned from the results of political attitude surveys conducted by the National Democratic Institute (NDI). While grossly missing out on the actual voting results in 2016, the survey clearly shows a relative tendency among rural voters to refuse to state their political preferences (“no party,” “don’t know,” “refuse to answer”). The share of those not stating their political preferences was lowest in the capital (46%), followed by large cities (56%), and predominantly rural municipalities (61%). It was highest in ethnic minority municipalities (63%).

We already know that in reality rural voters tend to bet on the incumbents (UNM in 2012 and GD in 2016). What we learn from the NDI survey is that, being most dependent on handouts by the central government, rural and ethnic minority voters are not willing to take the risk of exposing their pro-government preferences to survey takers who, they think, might represent, or share information with, the opposition forces.

One could try to explain the radical change in rural electorate's political preferences in 2016 parliamentary elections by GD's success in opening the Russian market for Georgia’s traditional agricultural products in summer 2013, and the drastic increase in the financing of agricultural programs targeting subsistence and semi-subsistence farmers. Yet, while certainly contributing to GD’s electoral victories in 2016 and 2017, the same factors (with a minus sign) did not prevent Saakashvili from securing another term in 2008 and winning a very large share of rural votes in 2012. Georgia’s rural voters tend to be pro-establishment voters even when the government in power does not deliver on their dreams of inclusive growth and prosperity.

What are the implications of these voting patterns for Georgia’s ability to generate democratic transitions? The intellectual and business elites in Tbilisi and (to a less extent) other major cities, such as Batumi and Kutaisi, clearly play a key role in generating political change. Georgia’s 2003 Rose Revolution was won in Tbilisi, not the Georgian countryside. In 2012, Tbilisi overwhelmingly supported Bidzina Ivanishvili’s GD coalition while rural Georgians were still willing to vote for UNM.

Conservative pro-establishment forces get stronger in traditional, rural areas where people’s political agendas are dominated by purely local concerns – access to utilities, jobs, health and education services (provided by the central government). The pro-establishment vote is most pronounced in ethnic minority-dominated municipalities along Georgia’s southern borders, where people’s attitude towards national policy matters (as opposed to local ones) is best characterized by indifference and apathy.

Georgia’s most recent local elections suggest that Tbilisi (and, by extension, Georgia as a whole) is not yet ripe for another political transition. Kakha Kaladze, a former football star and GD’s energy minister, may be an exceptionally popular candidate, yet his first round victory in Tbilisi’s mayoral race suggests that Georgia’s capital is still solidly blue. Furthermore, NDI surveys and the actual election results indicate that the opposition forces – while quite vocal – are hopelessly divided. In the absence of a strong unifying opposition leader, it is much easier for GD to win in those areas, where the majority of people would have preferred an alternative to the status quo.

Strong leaders have always been a crucial factor in Georgian politics. Ruling coalitions and parties have been held together by powerful (formal or informal) leaders: Shevardnadze from 1992/3 until 2003, Saakashvili from 2003/4 until 2013, and Bidzina Ivanishvili since 2012. The latter remains at the helm of GD even after resigning from his official positions in 2013. As the éminence grise of Georgia, he appears to be perfectly capable of maintaining GD’s unity and political domination in the foreseeable future.

* * *

In the short term, the tendency of rural Georgians to stand by the incumbents is a stabilizing factor. It certainly allows new governments to consolidate their power and implement an ambitious reform agenda, should they wish to do so. In the medium term, however, this very tendency detracts from the vibrancy of Georgia’s democracy. First, it puts the emerging forces of change in Tbilisi and the country’s major urban centers at a disadvantage when it comes to formal channels of influencing policy outcomes, raising the political temperature and creating a fertile ground for destabilizing, violent forms of political expression. Second, it weakens the government’s democratic accountability and reduces its appetite for participatory democratic processes and sound, welfare-enhancing reforms.

The planned reform of Georgia’s electoral law, which in its current form facilitates the emergence of parliamentary super-majorities, is quite likely to create a healthier situation in which major political choices are more rigorously contested. However, it would be foolish to assume that any such reform alone would turn Georgia into a full-blown democracy. It will take a protracted civil education effort for the Georgian rural population to more fully embrace democratic freedoms and independently and fearlessly exercise their democratic rights.