18

December

2023

18

December

2023

ISET Economist Blog

Monday,

19

October,

2020

Monday,

19

October,

2020

Monday,

19

October,

2020

Monday,

19

October,

2020

When the Georgian unemployment statistics for Quarter 2 (April, May, June) of 2020 came out, no one was surprised to see that the national unemployment rate, which had been falling steadily over the previous quarters, and even years, suddenly increased by 0.9 percentage points relative to the same quarter of 2019 (more precisely from 11.4% in Q2 2019 to 12.3% in Q2 2020). Perhaps we were more surprised by the fact that the unemployment rate did not go up more drastically in the midst of a strict lockdown, various travel restrictions, and quarantine measures. The economy shed “just” 43.8 thousand hired workers; an additional 9.6 thousand became “self-employed”, and an additional 15.6 thousand people joined the ranks of the unemployed.

The relatively mild increase in the unemployment rate in Q2 2020 can be better understood if we keep in mind how unemployment data is collected in Georgia. In accordance with internationally accepted methodology, the quarterly labor force survey asks people a series of questions about their employment status over the last 7 days. For statistical purposes, a person is considered employed if he or she has worked for at least 1 hour during the last 7 days for payment, or in a family farm/business without pay. The person is considered unemployed if he or she has not worked for even 1 hour during the last 7 days, was actively looking for work in the past 4 weeks, and was available to start work within the next 2 weeks. Thus, these statistics typically mask the undesired loss of work hours, pay cuts, and/or forced leaves without pay. In addition, the unemployment rate may increase for two reasons: some people may have lost their jobs, but others who were previously economically inactive may have decided to join the labor force and were actively looking for work.

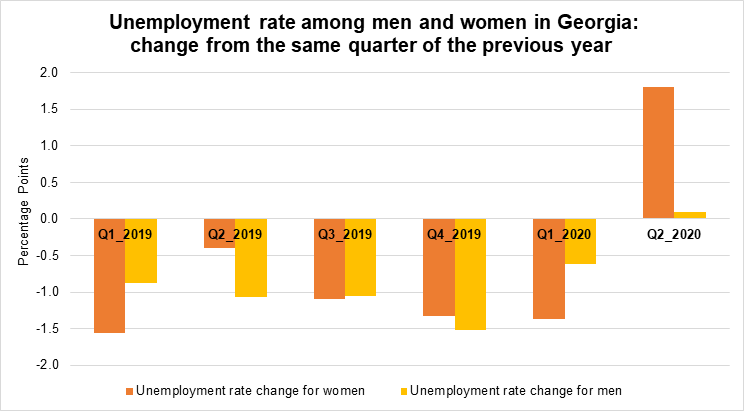

Yet, the Q2 unemployment statistics contained one shocking feature: of the 15.6 thousand “new” unemployed, 13.9 thousand (89%) were women, and only 1.7 thousand (11%) were men. In fact, the male unemployment rate increased by only 0.1 percentage points, while the female unemployment rate increased by 1.8 percentage points relative to Q2 2019.

Figure 1. Unemployment increase in Georgia

Of course, in the absence of longer quarterly employment series, the result is harder to put into context. In fact, it could be due to some peculiarity of the data. For example, employment and unemployment numbers may change quite significantly from quarter to quarter (due to the seasonal nature of jobs) or between the same quarters in different years (due to the changing structure of the economy). For our purposes, comparing Quarter 2 of 2019 and 2020 would remove the seasonality effect, but it may not completely ensure that women’s share in unemployment was not due to reasons other than the COVID-19 lockdown.

Nevertheless, it is easy to see that the female unemployment rate, which had shown a declining trend in the previous quarters, experienced a considerable spike during the COVID-19 lockdown period.

Figure 2. Change in the unemployment rate, relative to the same quarter of the previous year

At the same time, the data also tells us that the ranks of self-employed in Q2 2020 were swelled mostly due to women (out of the 9.6 thousand additional self-employed, 95%, or 9.1 thousand, were women). Even more dramatically, the 43.8 thousand hired employees who lost their jobs were overwhelmingly women (99%). There were 43.4 thousand fewer women in hired employment from Quarter 2 of 2019 to 2020, compared to just 0.4 thousand fewer men).

If we disregard the possible data peculiarities mentioned earlier, how can we explain such a shocking loss of hired employment among women, but not among men during the “great lockdown” period?

The most obvious hypothesis is that the sectors which were most affected by the lockdown were also the sectors that disproportionately employed women. While it is still difficult to precisely measure the effect, it would be fair to say that service sectors were affected the most (e.g. hotels and restaurants either stopped working during the lockdown or were severely limited in their activities; other service sectors, such as retail trade, which mostly require face-to-face interaction, likewise largely stopped functioning). While sectors such as transportation (commercial freight), construction, and agriculture continued operating, although with limitations. A quick look at the 2018 statistics on employment (Geostat, Business Statistics) indeed shows that a number of sectors where women are more represented relative to the average were also those which likely suffered the most from the lockdown: accommodation and food services activities; (54% women, 46% men); arts, entertainment and recreation (47% women, 53% men); other service activities (56% women, 44% men) compared to the average of 40% women and 60% men across all sectors represented in the business statistics. The sectors mentioned above collectively employed 37.9 thousand women in 2018, with accommodation and food services employing 24.7 thousand. Another reason for the higher increase in the unemployment rate among women could be the spike of unemployment among domestic workers, who are mostly women (around 99% in 2019 ). It is possible that employment among domestic cleaners, cooks, and nannies suffered considerably during the lockdown and could have been the reason for the 89% share of women among the “new” unemployed.

Why are these issues important? From the economic policy point of view, numerous economic studies confirm that providing equal economic opportunities for men and women in the labor market can significantly contribute to the country’s economic growth in the long run and help reduce poverty. In recent years Georgia has made significant progress towards gender equality. Thus, it will be important to track the impact of COVID-19 on gender employment patterns, to make sure that the progress in this area is not derailed by the epidemic.